As a young Indigenous journalist, I must understand my history and culture so I can amplify the voices of my community and ensure their stories are being told in a way that allows Indigenous Peoples to control their narrative.

The old Mohawk Institute Residential School stands alone in a neighbourhood littered with big empty buildings in Brantford, Ontario. It’s secluded by the trees and the land that it stands on, almost as if it’s completely withdrawn from the town that surrounds it.

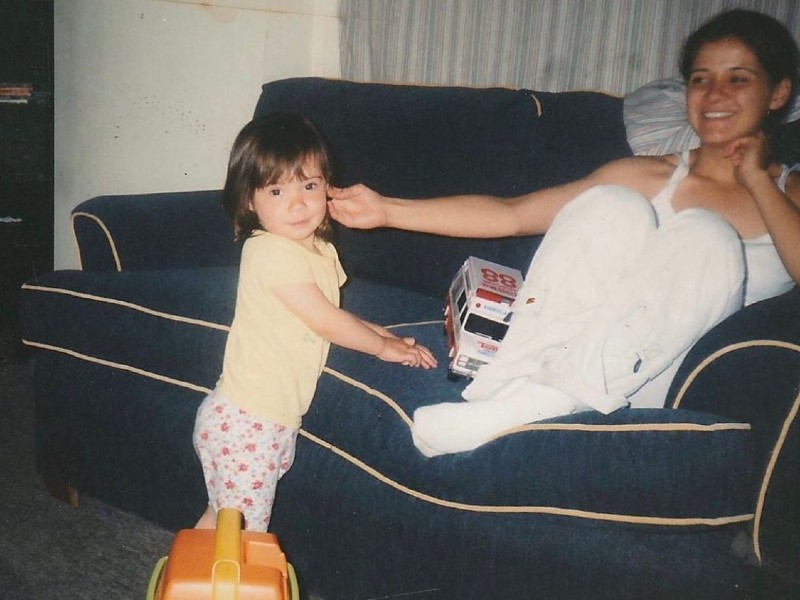

Growing up, the house that I was practically raised in was just minutes down the road. I remember driving by the building with my aunt to get gas from the Six Nations Reserve and every time I spotted the school from the backseat of the minivan it gave me the creeps. However, back then, I had no knowledge of residential schools, no understanding of how that part of Canada’s history had directly impacted my family, and I didn’t even know what the term ‘Indian’ meant. You could say the residential school system succeeded in disconnecting my family and me from our traditional Ojibwe identity and culture.

Flash-forward many years to September 2021 when I entered my first year at Toronto Metropolitan University’s School of Journalism. I noticed the effort that was put in to educate all of the journalism students on Indigenous history. For the first time in my life, I was learning the history of my people from members of the Indigenous community.

After hearing stories from other Indigenous journalists and learning about their experiences, I knew where my journalism career was going. I felt the responsibility to help my people tell their stories. I felt the responsibility to relearn my history and culture. I was going to take it into my own hands and finally fill in the missing puzzle-pieces.

When it came time to write my first story, I chose something that was close to my heart: the Mohawk Institute, and how the community was preparing for the ground search for children who did not survive the former residential school. Mohawk Institute Residential School operated for over a century with thousands of Indigenous students attending the school throughout this time period. The children who attended this institution were from First Nations communities across Canada, but a majority of them were from Haudenosaunee communities.

The discoveries of unmarked graves at former residential schools across Canada was a significant time in my life. It was the first time I ever heard my grandmother speak about her mother and how she was a Survivor. Covering this topic was my first experience as a young Indigenous journalist reporting on a subject that brought up a lot of personal pain and trauma. This experience also helped me understand the intergenerational effects of residential schools that impact families like mine, to this day.

My second story about the Institute included a tour of the building and the Woodland Cultural Centre. As the car slowly inched up the extended driveway and pulled up to the front of the building, I suddenly felt anxious and nervous. As I toured the school I couldn’t help but glance out the windows and think about how it felt as if time was standing still. The school appeared to be isolated from any form of life. I thought about the resiliency of my people and how hard they have fought and continue to fight to preserve their culture, language, and rights.

I realized that this is my ‘why.’ Everything I felt throughout the tour is the reason why I wanted to work alongside my community. It’s why I have so much respect for my community. We stand together and we share our stories to make each other stronger.

After the tour, many friends and family members asked me what it’s like to report on something like the old Mohawk Institute, but, if I’m being honest, that’s not an easy question to answer. As a journalist, I am expected to remove my bias and emotions from the equation, but as a member of the Indigenous community, that’s easier said than done.

When I first sat down to write, it took me a long time to form any words. I had to analyze a lot of emotions and life experiences because for a long time I had invalidated my experience as a young Indigenous woman. I didn’t know if my story really mattered.

I am fighting to learn my history and culture so that I can be an active member of my community and, finally, I am starting to break my own intergenerational curses.

So when people ask me about my experience touring the old Mohawk Institute, my mind wanders to the little girl in the back seat of the minivan and how long of a journey it was for her to get to the end of this story.

**Clarification: Information clarifying the author’s Indigenous identity was added after the story was first posted.