This is the first in a two-part series highlighting works done by the next generation of Indigenous filmmakers, who are blazing their own path in the industry and bringing Indigenous ways of knowing, being and storytelling to the forefront.

Carrie Davis, a recent graduate from Toronto Metropolitan University’s Documentary Media MFA program, is using their own experience as a part of the generation of Indigenous children that was impacted by the Sixties Scoop to fuel their art and spread an important message.

They described their film Double M Country as a “reconnection to land, language and culture.” Davis is Moose Cree, Anishinaabe and English.

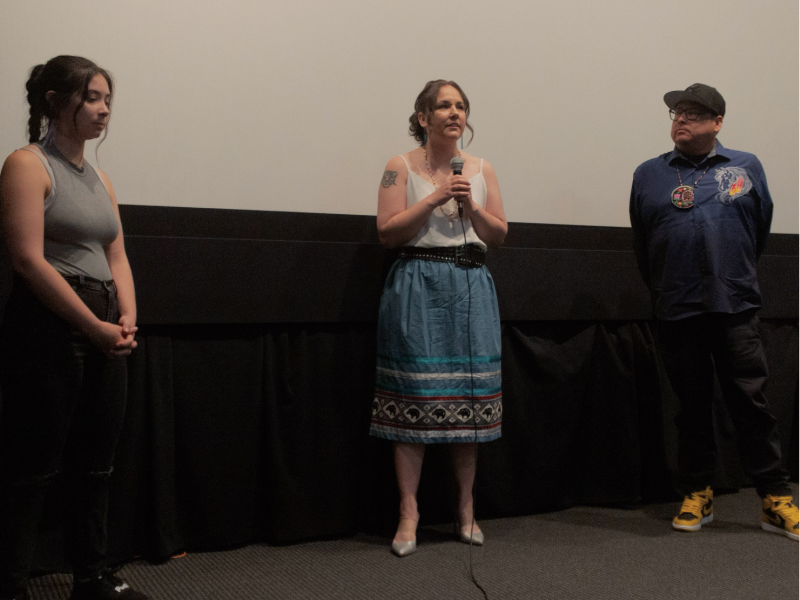

Davis’ short documentary premiered this summer, at the Doc Now documentary media festival hosted at the Imagine Carlton Cinema. In the intro to the film Davis shows the photo book of their early life that the government gave their foster family, after separating them from their birth family, their community and their culture. Davis said the photo book helped them trace their birth parents later in life.

“They had whited out the last names, so for a long time I didn’t know, but I was reading a Nancy Drew novel, and it said you could hold it up backwards to the light and you could see it, so I did that and I found out what my real last name was.”

The Sixties Scoop refers to the mass removal of Indigenous children from their families, and communities. They were then put into the child welfare system. In most cases the children were removed without consent from their families, or their band.

After Davis discovered the names under the white out, they began to piece together where the people in the photos came from.. They reached out to their birth mother on Facebook, and that was what sparked not only a journey of reconnection for Davis, but the making of Double M Country.

“I said this from the start, that this was a selfish endeavor. I really wanted to do my own story because I really wanted to go home. I have wanted to go home since 2012, when I met my birth family over Facebook,” said Davis.

It was also important to Davis to film their own journey because the reconnection and reclamation of community, culture and language for Indigenous Peoples that have been separated from their families as a child is a raw and sensitive experience.

“You don’t know what’s going to happen in these films. And some people don’t have a good experience going home,” said Davis.

Davis shared that part of the important work leading up to the production of this film and returning to their home community started with their own healing journey. Davis overcame their substance use, and started prioritizing their mental health. Davis believes this contributed to the good experience they had going home to Moose Factory.

Davis followed the advice of one of their film heroes, Tasha Hubbard, who tells young filmmakers to build a continuous relationship of reciprocity and respect within the communities they enter, and to continue these relationships after they leave.

“So it was important to me that if I was going to go to Moose Factory and do this film and learn about my community, and have people teaching me, I would continue to have that relationship. And so the last time that I went up, I even just reached out to people before I came and asked if they needed anything before I came back up. Because it’s way cheaper to go to a Walmart in Toronto, than it is to go to a reserve. Like a bag of chips can be $10 on a reserve,” said Davis.

Creating a relationship built on respect, trust and reciprocity is something that storytellers of all different kinds can aspire to follow. Davis believes this is especially something that journalists and documentary filmmakers should prioritize during their work, due to these two industries repeatedly going into Indigenous communities and taking stories.

As the film follows Davis’ reconnection journey to their ancestors’ traditional lands and culture, Double M Country captures this reclamation through Indigenous ways of storytelling, knowing and being.

“Our ways are really thoughtful and ethical. We should be living these ways of knowing and being in our regular lives,” said Davis, “but beyond that I think these kinds of ways of knowing and being were taken away from us and weren’t respected.”

Throughout the process of making this film and reconnecting with their home community, family, culture and language, Davis found a sense of belonging that had been missing for many years.

“When I went back to Moose Factory and suddenly I felt this calmness inside me, I felt okay, like I belonged here. My whole life I had been searching for somewhere to belong.”

And this reminded Davis of the words of advice they received from Sarah Wright Cardinal, a research associate in the faculty of Education at University of Victoria, who said: “It’s a deep knowing in your blood that you know you belong there, and no one can take that away from you.” Although the filming and reconnection experience featured a lot of positive and empowering moments for Davis, there were also challenges.

“There’s a lot that goes behind the scenes that I didn’t put in my films. I wanted to say that story telling isn’t that easy.”

For Davis, part of the challenge was knowing what to put in the film and what to keep for themselves, because the film surrounds such a personal journey.

“I wanted this film not to just be about trauma, but also healing. So that’s why there’s more laughter in it, because with Indigenous people, healing is through our laughter. And I wanted to acknowledge the trauma experienced by the children and families of the Sixties Scoop.”

Double M Country is available for viewing from October 17 to the 22 during the 24th annual ImagineNATIVE Film and Media Arts Festival.